LMSA’s Progress in Cutting Carbon and Opportunities for Improvement: A Candid Conversation

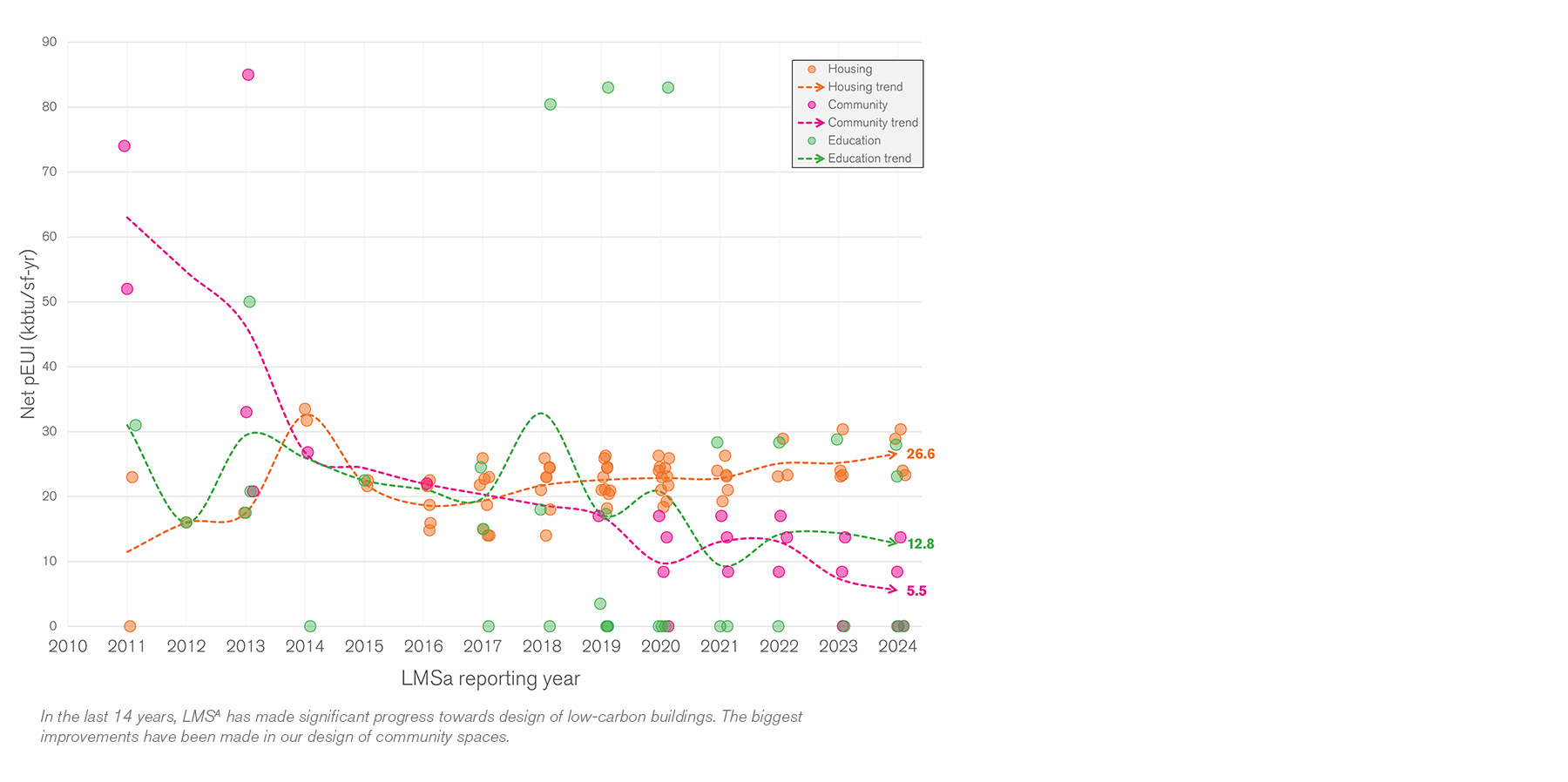

In its efforts to combat climate change, LMSA has tracked patterns and progress towards operational carbon reduction (the emissions related to heating, cooling and operating buildings) for over a decade. Fortunately, with building electrification and renewable energy sources, it is possible to design a building that doesn’t operate on fossil fuels, and LMSA is designing projects that cut fossil fuel across affordable/supportive housing, educational buildings, and community-focused spaces.

But huge amounts of fossil fuels are used to create building materials such as concrete and steel. Eleven percent of global carbon emissions come from the embodied carbon in those materials, which is emitted well before a project ever breaks ground.

Cutting embodied carbon is a whole new challenge, which is already implemented in CalGreen, with additional requirements being mandated by the State of California. To help figure out what can be done by designers, LMSA senior associate Gwen Fuertes recently connected with Meghan Lewis, an architect by training and a program director at the Carbon Leadership Forum, a Seattle-based nonprofit focused on getting embodied carbon down to zero.

Gwen: Architects have been aware for some time that we can’t just worry about energy use, we have to think about the carbon impact of building materials too. What is the low-hanging fruit of embodied carbon reduction these days?

Meghan: Cement, which is the binder that holds everything together in concrete, is one of the biggest culprits. So one way to reduce the amount of cement in your project is to reduce overdesign [when a building is over-engineered]. Just sharpen your pencils, as we like to say, and really make that a priority with the engineering team working on the project.

You can also use a range of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). There’s Type 1L cement, and an emerging material, LC3. There’s a lot of different strategies that can be summed up as, “Use less cement in your cement,” and then “Use less cement in your concrete.” You could work with your local concrete supplier and get up to a 30 percent reduction because they already know how to do that.

This also assumes you’ve already designed your building. You can also take a step back and get rid of cantilevers, for example. We’ve also seen a huge impact when designers eliminate underground structures, which comprise a huge proportion of embodied carbon in buildings.

There are structural engineering firms that are talking about using less and reducing the number of columns in their projects, and that is meaningful in terms of designing and building better. We’re just now seeing companies that are packaging material efficiency as a product and selling it. And I think there’s going to be a lot more of that.

For example, I just learned about a new precast structural product called Vaulted that optimizes the design by mimicking vaulted ceilings and cathedrals that requires a third of the cement and a tenth of the steel, so it’s a third of the emissions.

Gwen: We’ve started to experiment with some of the newer concrete mixes. We're doing these tests in areas of the building that aren't structurally necessary, like topping slabs. I don’t know all the details, but some of the new mixes haven’t all worked out. We are clearly in this era of innovation where products are not quite fully fleshed out, but there’s a lot of potential. Are there other things we can look at besides cement?

Meghan: Insulation is another big one. I’m really excited about a refrigerant ban for certain foams that came out in January. Avoiding the use of insulation with the highest GHG [greenhouse gases] has a really big impact as well.

Gwen: We’ve also started to experiment with mass timber. We have a new project, The Hub Community Center in Sunnydale, one of the first mass timber community centers on the West Coast, and the first in San Francisco. Anything you can share on that?

Meghan: Mass timber is so popular because it’s beautiful, and people associate positive things with a lower-carbon building. You don’t actually need the building to look different [to be less carbon-intensive], but that’s to its detriment in some ways. Being able to see a building and feel that it’s lower carbon is helpful for capturing interest.

Without including biogenic carbon [the carbon that is sequestered in wood], I’ve seen some projects that are reducing 30, 40 percent of global warming potential (GWP) by using mass timber. And others, not so much—like 5 percent. I think that partially has to do with policies; for example, if you have to cover the mass timber with tons of gypsum board to meet fire code.

Gwen: We’ve been participating in the AIA 2030 Commitment for 14 years now, trying to reach net-zero [zero operational carbon emissions by 2030]. Are there target reductions for embodied carbon?

Meghan: California has a state goal for reducing embodied carbon. Right now, CARB (California Air Resources Board) is establishing a methodology to set a baseline for embodied emissions for all of California. And then they have a legislatively mandated reduction target of 40 percent by 2035. They’re trying to figure out how to set that baseline meaningfully. And then they’ll be requiring reporting for EPDs [environmental product declarations] and whole building LCA [life cycle assessments], and have some sort of short-term easier reporting and long-term aspirations.

Gwen: Are there going to be different baselines for different building types, as is the case for operational carbon?

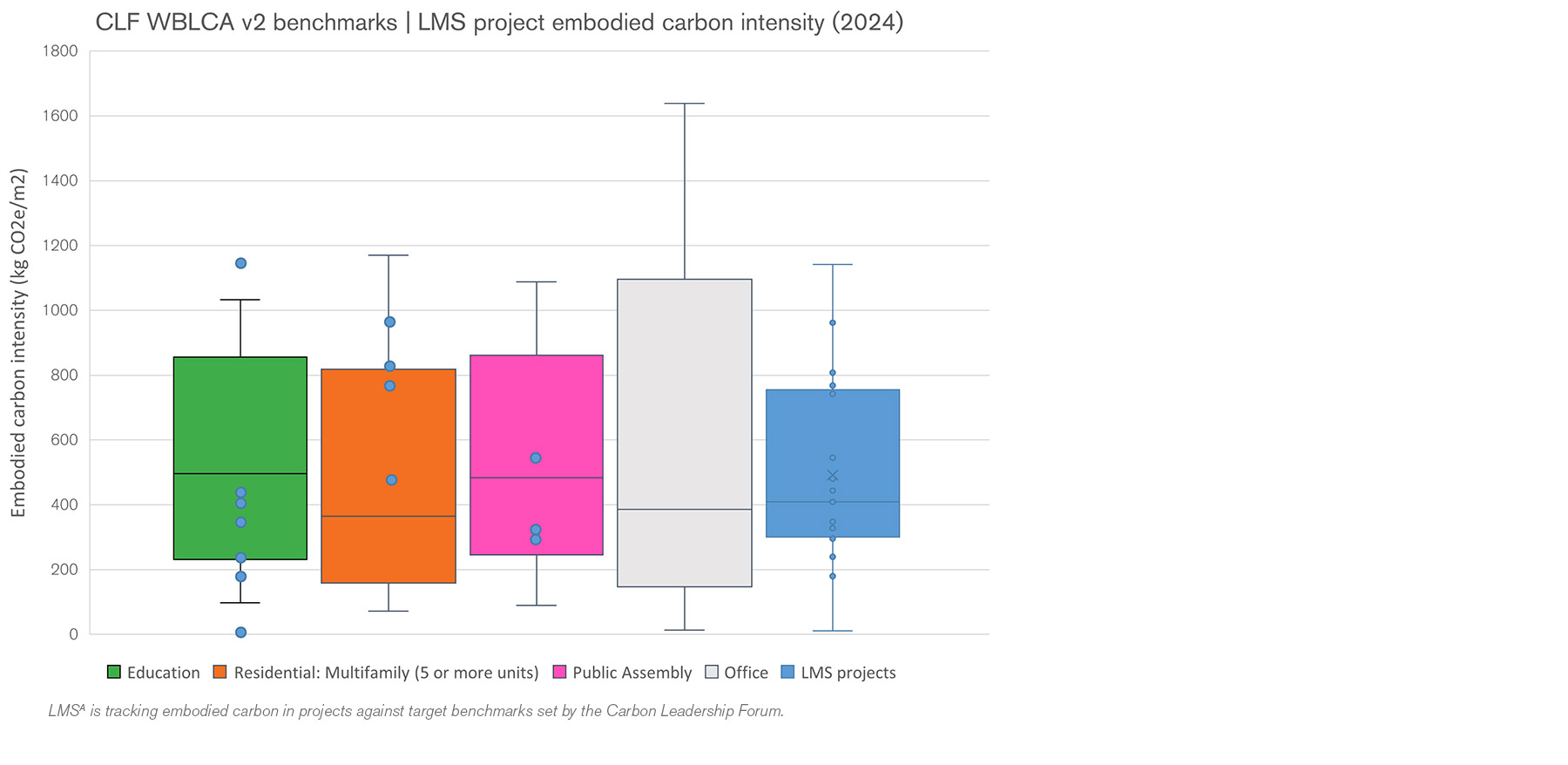

Meghan: We've just published our benchmarking numbers for embodied carbon, based on data from about 300 buildings from 30 firms across North America. We really see that building use-type does matter. We're recommending benchmarks for six different categories: warehouse and storage, multifamily residential, education, office, public assembly, and an “other” category.

We expect these to be used by policy makers pretty much immediately, to have an alternative to the existing pathway—which is to say, reduction from a baseline building. Instead, you have an embodied carbon intensity target. We’re presenting the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles for each building use type. If you’re a developer and you get to add an entire floor to your multifamily building because you reach this benchmark, then it should be lower than if it’s “all buildings in California.”

Gwen: What does the timeline look like for getting to zero embodied carbon? Will we have a five-year goal like Architecture 2030?

Meghan: In the next five years, I’d like to see us in a place where, other than understanding how to measure embodied carbon, teams are really focusing on what they can to quickly reduce embodied carbon on a project—the low-hanging fruit we talked about. And then in 2040, we’re getting to the point where we’ve already achieved a lot of those basic strategies. In the last ten years, that’s when you really need some of the developing technologies and novel materials that are not scaled right now. We’re aiming for 2050 instead of 2030.

Gwen: Firms like ours are invested, we really care, but it feels kind of overwhelming to tackle everything at once. The more we can break it down into pieces like the Architecture 2030 commitment, the better: starting with 40 percent reduction, 50, 60, and then suddenly we’re at 100. It goes from awareness to literacy to being super-fluent—having all the levers at our disposal and knowing how to push every one. And not having to necessarily run a whole-building LCA in order to do that.

Meghan: Outside of targets and benchmarks is piloting new technology, like experimenting with topping slabs. On the scale of your project, it probably didn't help you that much [to reduce embodied carbon], but I think that that's still a really meaningful action to take on a project. It's really hard for those companies to find pilots and to have a partner who actually wants to test that out. And we still need that right now. We’re still investing in bigger reductions in the long term for some of these things.

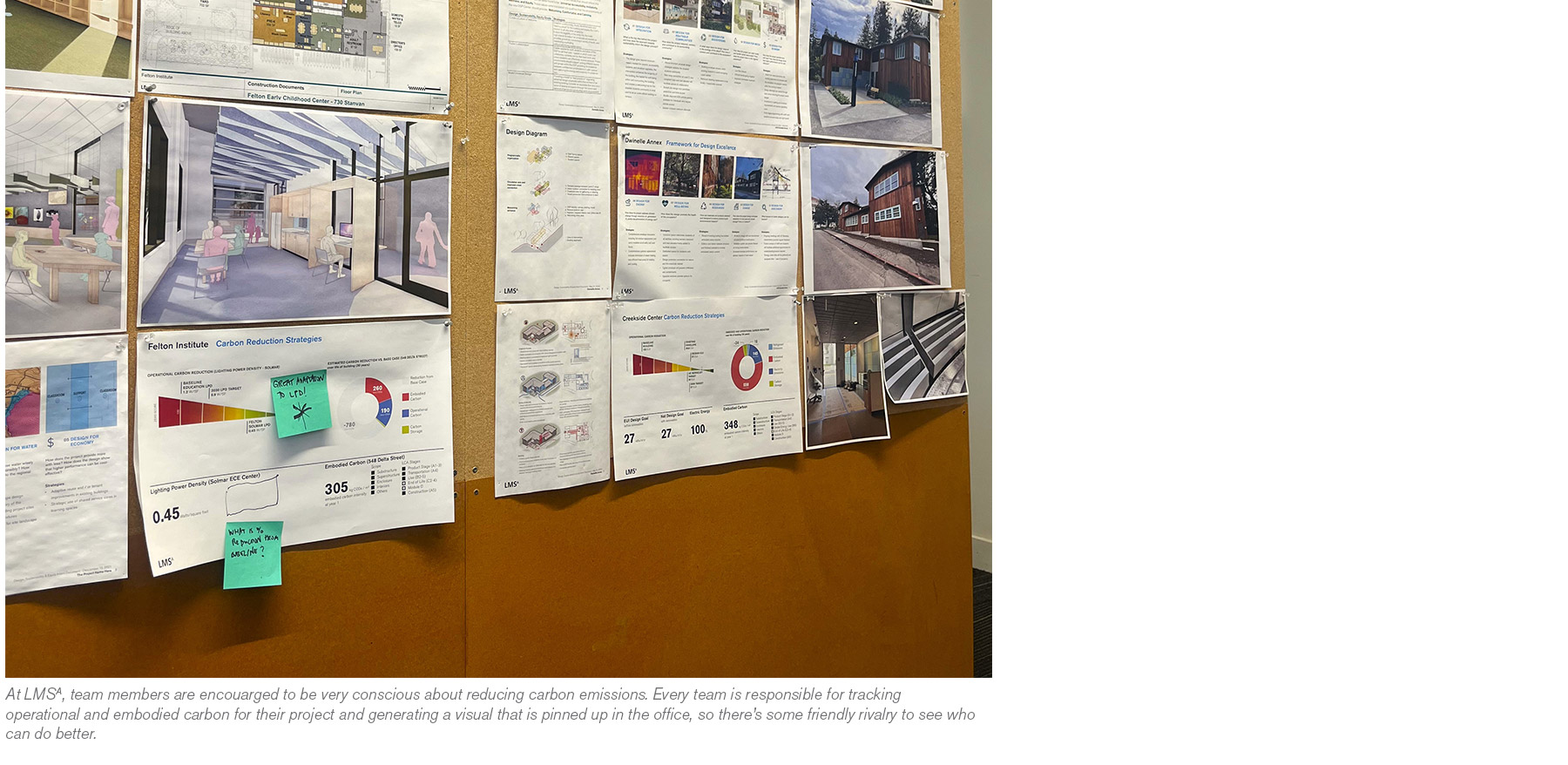

A big thank you to Meghan for her time and insights! 2025 marks LMSA’s 14th year of reporting for the AIA National 2030 Commitment. This year, five projects met the commitment target of 80%+ reduction toward net-zero, including Sunnydale Community Center, Mosswood Community Center, University High School, Nueva Arts & Administration Building, and UC Berkeley’s Creekside Center. We also reported 16 projects with embodied carbon data this year, more than any previous year. We are digesting the results and are eager to dive deeper into the data in an effort to continue our path to net-zero and carbon reduction.