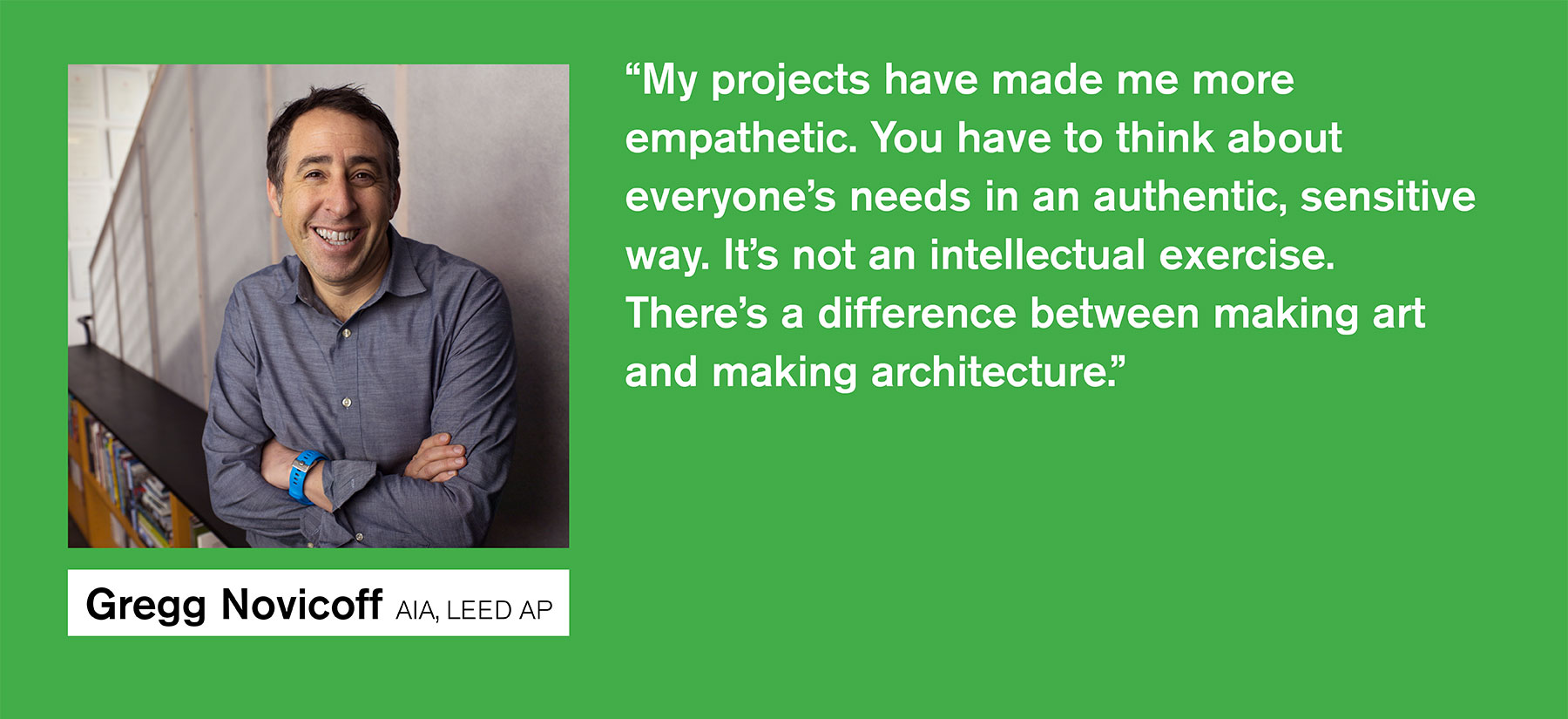

LMSA Principal Gregg Novicoff discusses designing with empathy, navigating public process, and how labor unions shaped his progressive values.

Q: What led you to become an architect?

My life has seemed to have been focused on building community. That’s why I live in the city. I love our city, its straight, curved and crooked streets. The neighborhoods, from Sunnydale to Ocean Beach to the Ferry Building. I love the San Francisco Giants, I love the diversity. I know we have all been shut in for a year, but I’m looking forward to seeing my neighbors out in our streets, stores, parks and cafes. I want to see everyone thrive together in an egalitarian community.

Q: Did you grow up here?

I grew up in Los Angeles. My grandparents found their way there from Russia—they were fleeing the pogroms. My grandfather managed a market and my uncle became a union organizer. My first job was at a supermarket, and I was part of the United Food and Commercial Workers union—paid $75 for my union card. Then I went to Cal. So I grew up with progressive values.

Q: How did you end up at Leddy Maytum Stacy Architects?

I first found out about LMSA from the 1991 SFMOMA show- In the Spirit of Modernism at the War Memorial that I went to when I was an undergraduate.. All the work at the show struck me, and at the time, if you wanted to be an architect in the Bay Area, and you didn’t have an interest in postmodernism, there were only about five firms you could choose from. Later on, I went to work in New York, went to graduate school, and knew I wanted to come back to San Francisco. I worked for a Russ Drinker at MBT and Cathy Simon at SMWM, and then I joined LMSA in 2005.

Q: Sometimes the public process on projects can be contentious. How do you navigate that?

People appreciate hearing the truth and having someone respect them to speak honestly about what they or I can or cannot influence. I try to be clear on what we are asking- Can the public decide? Or is it a partnership? Or are we just informing? People react positively where the conversation is and that you’re not sugarcoating anything. I want to start early, engage them at the beginning and build trust.

Q: Is there a project that, when it was completed, surprised you in some way?

I have been incredibly fortunate to work on a number of projects that have impacted me. From the Ed Robert’s Campus to now on the Sunnydale Community and Recreation Centers for Mercy, Related and SFRPD. But, the Nancy and Stephen Grand Family House may be the most powerful project I’ve worked on. It provides temporary housing for children who are being treated at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Benioff Children’s Hospital, as well as for their families. Every time I visit there and talk to people, they have been so appreciative and thankful. That speaks to the importance of making a place that builds community. It won a COTE Top Ten Green Projects Award. I’m incredibly proud of that project.

Q: Do you think the projects you’ve worked on have changed you?

Absolutely. I’m a better listener. They have made me more empathetic. You have to think about everyone’s needs in an authentic, sensitive way. It’s not an intellectual exercise. There’s a difference between making art and making architecture.

Q: Is there a project closest to your heart?

I don’t know how to answer that, because I love the eclecticism of our work. The radio program that I listen to weekend mornings, KCRW’s “Morning Becomes Eclectic,” goes from bossa nova to jazz to electronica to Haim. I love that. And I like that LMSA is always changing, the portfolio is always developing around its core values.

Q: If you hadn’t become an architect, what profession do you think you’d be in and why?

I love cities. I love walking the city streets. If I wasn’t an architect, I’d be doing something in the built environment. When I moved to New York City, I was working at Central Park Conservancy. It was amazing to work on the design and construction at Central Park, renovating Olmstead’s structures and building new ones, surveying the land, driving around in a little green truck, ice skating at lunch in the wintertime. If I wasn’t an architect, it might not be so bad to be in that truck again.